Barabbas

Theology 101 continues its peek behind the scenes of some of the prominent figures, groups and events referenced in the Bible. The goal is to provide a deeper context for the drama of salvation that sacred Scripture communicates to us.

Theology 101 continues its peek behind the scenes of some of the prominent figures, groups and events referenced in the Bible. The goal is to provide a deeper context for the drama of salvation that sacred Scripture communicates to us.

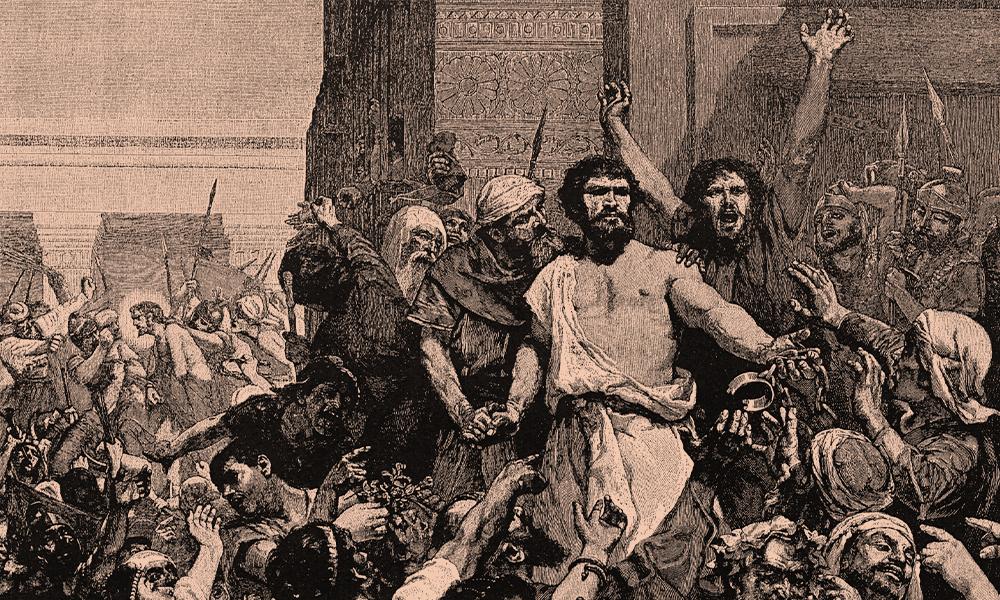

Now on the occasion of the feast [Pilate] used to release to them one prisoner whom they requested. A man called Barabbas was then in prison along with the rebels who had committed murder in a rebellion. The crowd came forward and began to ask him to do for them as he was accustomed. Pilate answered, “Do you want me to release to you the king of the Jews?” For he knew that it was out of envy that the chief priests had handed him over. But the chief priests stirred up the crowd to have him release Barabbas for them instead.

Pilate again said to them in reply, “Then what [do you want] me to do with [the man you call] the king of the Jews?” They shouted again, “Crucify him.” Pilate said to them, “Why? What evil has he done?” They only shouted the louder, “Crucify him.” So Pilate, wishing to satisfy the crowd, released Barabbas to them and, after he had Jesus scourged, handed him over to be crucified. (Mk 15:6-15)

We do not know much about Barabbas apart from what can be derived from Scripture. Despite this, the story of Barabbas’ selection by the crowd and his subsequent liberation holds great spiritual value for us today.

Great expectations

All four Gospel writers tell us that Barabbas was the prisoner Pontius Pilate pardoned as part of a custom that preceded the Passover feast. As we see in the passage above, Pilate had let the crowd choose the person who would receive the pardon. From our current vantage point, the choice between Barabbas and Jesus of Nazareth seems obvious. The two could not be more different. However, the case was more complex than it might first appear.

Both prisoners presented to the crowd were considered subversives by the civil authorities. Jesus of Nazareth was accused of claiming to be the King of the Jews in defiance of Rome’s rule. Barabbas, on the other hand, had been captured by the Romans for his part in an armed insurrection. Both were considered threats to the civil order and faced the same charge of treason.

Further, Jesus of Nazareth had threatened the religious authorities by his claims to being the “Son of the Eternal Father,” his cleansing of the temple, and his talk about the temple being destroyed and rebuilt in three days.

His entry to Jerusalem to shouts of “Hosanna, son of David!” amounted to a clear declaration of the people’s belief that Jesus was indeed the promised messiah, or savior, of the Jewish nation. Here, at last, the crowd had a clear distinction between Jesus and Barabbas, right?

Not quite. In the first volume of Pope Benedict XVI’s Jesus of Nazareth, the pope emeritus notes that Origen, an early Church Father, maintained that many manuscripts of the Gospels identified Barabbas as “Jesus Barabbas” until the third century. Bar-Abbas means “son of the father,” and “son of the father” was a title attributed to messianic – or those presumed to be the messiah – figures. Pope Benedict XVI also observes that the Gospel of Matthew describes Barabbas as “a notorious prisoner.” He cites this as evidence that Barabbas held a prominent place in the resistance and argues that Barabbas was likely the leader of the uprising that had landed him in prison.

These points taken together, the pope asserts, suggest Barabbas was also a messianic figure. That is, like Jesus, some people believed Barabbas to be the promised and expected deliverer of the Jewish people. So, not only were Jesus and Barabbas charged with the same crime, they may have shared the same first name, and been assigned the same title. (Though Jesus of Nazareth is the only one to have claimed – accurately, we might add – the title for himself.)

Pope Benedict XVI concludes that in choosing Barabbas, the crowd chose a savior who “leads an armed struggle, promises freedom and a kingdom of one’s own” over a Savior “who proclaims that losing oneself is the way to life.” The decision for Barabbas, perhaps, had more to do with the crowd’s expectation of what kind of person the savior would be than other factors.

Sources:

New American Bible

Pope Benedict XVI, Jesus of Nazareth, Vol. 1

Did You Know…

In 1961, Anthony Quinn played Barabbas in the religious epic film of the same name. The movie, based on a 1950 novel by Nobel Prize-winning Pär Lagerkvist, explored the life of Barabbas after his pardon from Pontius Pilate. The film portrays a man haunted by the memory of Jesus who finally places his faith in Christ as he dies.

Did you know?

Pontius Pilate has the distinction of being the only person other than the members of the Trinity and the Virgin Mary to be mentioned by name in the Nicene Creed: “For our sake he was crucified under Pontius Pilate, he suffered death and was buried …” Why would this be? We must remember that the Creed was originally written as a defense against the heresies that plagued the early Church.

The framers of the Creed felt an imperative to address burgeoning heresies in the early Church. One such heresy was that some disputed the death of Jesus (and, by implication, his resurrection) as historical reality. The best way to refute this was to link the event to an actual historical figure. (Sister Janet Schaeffler, OP)

Bible Quiz

Each of the four Gospels refers to Barabbas differently, the Gospel of John calls him a…

A. Resistance Fighter

B. Robber

C. Notorious Prisoner

D. Accused Murderer

Answer: B – Robber

Doug Culp is the delegate for administration and the secretary for pastoral life for the Catholic Diocese of Lexington.